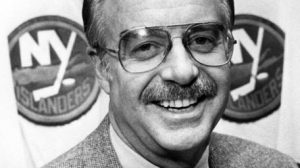

High in the rafters of Nassau Coliseum hang a pair of banners honoring two Islanders legends who never donned the blue and orange: general manager Bill Torrey and coach Al Arbour. Together these two men developed one of the most remarkable dynasties in NHL history—the only US-based franchise to win four straight Stanley Cup championships.

Fans of today’s Islanders can point with pride to another dynamic duo who have worked together to spark the Islanders’ resurgence in recent years: general manager Lou Lamoriello and coach Barry Trotz. Under their leadership a franchise that had won one playoff round between 1993 and 2018 suddenly played in the conference finals in their second year together, much like the Islanders did in 1975, the second year of the Torrey/Arbour collaboration.

In the two dozen years between Arbour’s departure in 1994 (except for one memorable game in 2007) and the hiring of Lamoriello and Trotz in 2018, the Islanders have struggled with their selections for general manager and coach: they fell far short of regaining the success they had enjoyed during the dynasty years. Comparing the Torrey-Arbour and Lamoriello-Trotz management teams reveals some similarities and some telling differences that remind us just how much the game has changed since the Isles’ last championship.

Lamoriello and Trotz arrived on Long Island with impressive NHL resumes. Lamoriello built three Stanley Cup winners in New Jersey before leaving to help rebuild a struggling Toronto Maple Leafs franchise in 2015, while Trotz was fresh off his first championship as coach of the Washington Capitals after fifteen seasons directing the Nashville Predators, taking them from expansion newborns to multiple playoff appearances. That was a far cry from the backgrounds of Torrey and Arbour.

Torrey had served as general manager of the Oakland Seals/California Golden Seals, leaving after he clashed with mercurial Charlie Finley, he of the white skates, while Arbour, after an admirable career as a steady defensive defenseman. Arbour had gone 42-40-25 over parts of three years as coach of the St. Louis Blues before being given his walking papers early in the 1972-73 season — the same year the Islanders entered the league. Thus neither Torrey nor Arbour brought to the Islanders the success enjoyed by Lamoriello and Trotz —although they would make up for it before long.

Arbour and Trotz had much in common when it came to coaching, focusing first on team defense. Each coach cut down the goals allowed by their team by one hundred goals in their first season behind the bench. Both relied on a two-goalie system, positional play on defense, and making sure that forwards forechecked and backchecked. Over time Arbour took advantage of talented offensive players to build a goal-scoring powerhouse featuring a lethal power play, but the Islanders excelled at shutting other teams down, including the Edmonton Oilers in the 1983 Stanley Cup Final. Whether Trotz can do the same remains to be seen: the Islander power play remains a team weakness, and Mat Barzal, exciting as he is, can’t be Bryan Trottier and Mike Bossy rolled into one.

(I don’t think Lou would allow this today.)

Torrey and Lamoriello faced radically different challenges in building their teams. The expansion draft of 1972 offered poor pickings for a first-year franchise, with only a handful of players (Billy Smith, Ed Westfall, and Gerry Hart) surviving to see the team become successful. Rather, Torrey depended on the draft to build a roster, a process that became easier because the Islanders’ low finishes their first two seasons gave them high draft picks (nine members of the Islanders’ 1980 championship roster were selected in the 1972, 1973, or 1974 drafts).

To be sure, Torrey was not always a skilled drafter—only one of his 1975 picks, Long Island’s own Richie Hanson, ever saw time with the Islanders. But in 1976 and 1977 he picked up five more eventual Stanley Cup champion-caliber players. Torrey proved equally able in making trades, obtaining J. P. Parise and Jude Drouin to bolster the team during its growing years: he would add eventual champions Jean Potvin, Bob Bourne, Wayne Merrick, Gord Lane, and most notably Butch Goring. Torrey also scoured Europe for players, with Stefan Persson and Anders Kallur (a free agent) the first players trained in Europe to have their names etched on the Cup.*

An impressive record, to be sure, but it was one achieved in a different world. Although teams signed the occasional free agent (usually an undrafted or released player), free agency as we know it today did not exist. Rather, Torrey had to concern himself with the rival World Hockey Association signing Islanders prospects: it was the appearance of that league (which helped explain why the Islanders came to exist in the first place) that drove up salaries. Nor did he have to worry himself about the salary cap. His Nassau Coliseum was brand-new, not aging or refurbished, although it belonged to an era before skyboxes or jumbo scoreboards. It was far easier to keep a team together: that sixteen players won four straight Stanley Cups is a feat unlikely to be replicated because the combination of the cap and free agency renders creating an maintaining a dynasty next to impossible (ask the Chicago Blackhawks, who have done as well as anyone under the circumstances). The National Hockey League Player Association was in its infancy; however, Torrey had to deal with an uncertain ownership situation (sound familiar?), as Roy Boe nearly ran the team into bankruptcy before Torrey facilitated the sale of the franchise to a group of investors led by John O. Pickett Jr.

Lamoriello operates in a different world, one ruled by cap considerations and global scouting.

No soon had he assumed his position than he lost the team’s 2009 #1 draft choice to the Maple Leafs through free agency; his own free agent signings have been largely role players with the exception of netminders Robin Lehner and Semyon Varlamov. To date he has been far less active than Torrey in trading for talent, securing Matt Martin, Andy Greene, and J-G Pageau. Of the drafts he’s supervised, only Oliver Wahlstrom and Noah Dobson, both drafted in 2018, have seen action with the team so far, although it’s too early to make an overall assessment. The salary cap restricts his ability to make deals, and it cost him Devon Toews. Four Cups in a row? No one’s won more than two in a row since 1983. It’s too early to determine whether Lamoriello’s ability to bring order out of chaos and to provide a clear direction for the team will translate to championship success. At least he has the support of a stable ownership group that seems determined to make the Islanders winners again in a state-of-the-art facility.

Like Torrey, Lamoriello holds fast to a vision of how to build a team for the long run, including an eye for the right fit (see Goring and Pageau). Just as Torrey worked in close collaboration with Arbour, Lamoriello has worked with Trotz.

Torrey and Arbour made their reputations with the Islanders: it remains to be seen whether Lamoriello and Trotz can replicate on Long Island what they have achieved elsewhere. Radar and the Bowtie have set a high standard.

Follow Brooks on Twitter at @BrooksDSimpson

Tags Al Arbour Barry Trotz Bill Torrey Lou lamoriello New York Islanders

Check Also

Bentivenga: Zdeno Chara returns to the Islanders on a one-year deal

June 23rd, 2001. Ex-Islanders general manager Mike Milbury pulled the trigger on a trade to ...

IBO Boxing Honesty and Integrity

IBO Boxing Honesty and Integrity