This week’s celebration of Memorial Day and the impending 75th anniversary of D-Day next week is the perfect time for a look at one of the 20th century’s most elusive baseball figures and World War II heroes, Moe Berg. It was said of Berg that he “spoke a dozen languages and couldn’t hit in any of them.” And while the new feature-length documentary The Spy Behind Home Plate gently notes that it was more like 10 languages, the point stands that Berg was a true “Renaissance Man,” for whom baseball took second priority only to his country.

This week’s celebration of Memorial Day and the impending 75th anniversary of D-Day next week is the perfect time for a look at one of the 20th century’s most elusive baseball figures and World War II heroes, Moe Berg. It was said of Berg that he “spoke a dozen languages and couldn’t hit in any of them.” And while the new feature-length documentary The Spy Behind Home Plate gently notes that it was more like 10 languages, the point stands that Berg was a true “Renaissance Man,” for whom baseball took second priority only to his country.

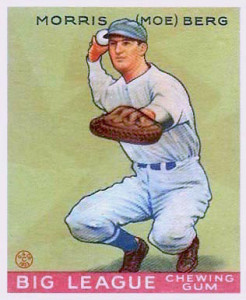

The film, screening in select theaters across the country Friday and throughout June, begins with Berg’s life in baseball, which was encouraged enthusiastically by his mother but not at all by his father, who expected his son to aspire to a career in law. But Moe, a star infielder whose strong arm gained him notice—as well as a spot as the only Jew on a local Church team—had designs on a career in the sport.

With New York’s Jewish population in mind, both Brooklyn and the N.Y. Giants made overtures to sign the Manhattan native. It was the Robins who won the sweepstakes in 1923, and the 21-year-old found himself at shortstop in Ebbetts field a few days later.

In part to appease his father, after graduating from Princeton, Berg studied law at Columbia. Scheduling conflicts almost cost him a spot on the White Sox, until capitulation by his professors allowed Berg to delay his classes and make up the work later. After passing the bar in 1929, Berg effectively had two jobs—half the year on the ballfield and half at a law firm.

In part to appease his father, after graduating from Princeton, Berg studied law at Columbia. Scheduling conflicts almost cost him a spot on the White Sox, until capitulation by his professors allowed Berg to delay his classes and make up the work later. After passing the bar in 1929, Berg effectively had two jobs—half the year on the ballfield and half at a law firm.

It was a couple of years earlier that the light-hitting (.243 career average, 49 career OPS+) Berg’s career took a most fortunate turn. Now with the White Sox after a 1925 waiver deal, with all of the team’s catchers injured, Berg took a turn behind the plate, at which he was quite adept. His days in the infield were over; Berg would appear at catcher exclusively the rest of his 15-year career, save a two-inning stint very late.

A fine handler of pitchers—and players in general—Berg would have made an outstanding coach and manager. Instead, his intellect and interests drove him to a far more fulfilling—and for the nation a far more important—role.

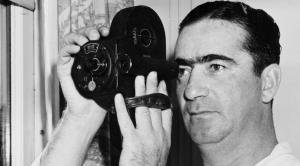

This is where The Spy Behind Home Plate moves from baseball to Berg’s clandestine work for the U.S. government. Two baseball trips to Japan, the second the famous 1934 tour that featured Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and a true All-Star team, set Berg on this course. Tales of his off-the-field work with his Bell and Howell movie camera, which included some deft work to reach the high tower of a Tokyo hotel for some pans of the city, are told in delightful detail by several of the interview subjects, including ex-players and an OSS agent.

This is where The Spy Behind Home Plate moves from baseball to Berg’s clandestine work for the U.S. government. Two baseball trips to Japan, the second the famous 1934 tour that featured Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and a true All-Star team, set Berg on this course. Tales of his off-the-field work with his Bell and Howell movie camera, which included some deft work to reach the high tower of a Tokyo hotel for some pans of the city, are told in delightful detail by several of the interview subjects, including ex-players and an OSS agent.

Berg also gained fame for appearances on the “Information Please” radio program. Later, his success there and connections with the producers were important in a radio broadcast he made to the Japanese people after the outbreak of World War II.

The film goes into several important Berg missions, notably his work in South America and Switzerland, during which he helped determine the extent (or lack thereof) of German work with nuclear fission in a pivotal time during which the race to manufacture an atomic bomb would largely determine the world’s future.

The film goes into several important Berg missions, notably his work in South America and Switzerland, during which he helped determine the extent (or lack thereof) of German work with nuclear fission in a pivotal time during which the race to manufacture an atomic bomb would largely determine the world’s future.

It’s a fascinating look at a pivotal time in the country, with the added intrigue of this unique American whose work no doubt changed history.

IBO Boxing Honesty and Integrity

IBO Boxing Honesty and Integrity