Baseball fans know 1968 as “The Year of the Pitcher”—batting averages and ERAs looked like those of the Deadball Era across the board, led by the last 30 game winner, Denny McLain of the Tigers, and the MLB record 1.12 ERA of the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson.

Baseball fans know 1968 as “The Year of the Pitcher”—batting averages and ERAs looked like those of the Deadball Era across the board, led by the last 30 game winner, Denny McLain of the Tigers, and the MLB record 1.12 ERA of the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson.

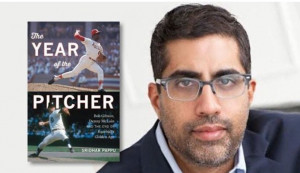

Those two big personalities are at the forefront of New York Times columnist Sridhar Pappu‘s chronicle of that season, The Year of the Pitcher: Bob Gibson, Denny McLain, and the End of Baseball’s Golden Age. The two top hurlers in the game that year led their respective teams to the World Series, matching up twice in the Fall Classic. Though Gibson bested McLain in Game 1 and Game 4, it was McLain’s Tigers who beat Gibson in Game 7, with Mickey Lolich edging the future Hall of Famer after McLain won Game 6.

The days of pitchers starting three games in a World Series have passed, as have 300-inning seasons—McLain (336) and Gibson (304 2/3) were among four who reached that mark in 1968. Indeed, rules changes the next year began to tilt the scales back towards hitters. And a half-century later, as fans remember a tumultuous social and political year, thoughts of the success of Gibson and McLain, and pitchers in general, dominate.

Pappu spoke with Sports Media Report about the year and his acclaimed book.

Sports Media Report: What do you think led to pitching being so dominant in the ’60s, with 1968 at the top of that list?

Sridhar Pappu: We have to remember this was not the case at the beginning of the decade. But one can easily trace the great pitching of 1968 back to the terrific seasons put up by Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle in their pursuit of Babe Ruth’s Home Run record in 1961. This was compounded by Tommy Davis’ 1962 campaign for the Dodgers. The forces that controlled baseball, believing that offense had caused the game to suffer, began putting rules in place to restore balance to the game. But it was an overreaction. As the 1960s wore on, one could see pitchers begin to dominate, culminating in 1968 when hitters were hindered by the rules and by great pitchers like Bob Gibson, Denny McLain, Don Drysdale and others using the rules to their advantage.

SMR: Nothing happens in a vacuum, but fans often have difficulty, especially 50 years later, remembering that. What are some ways that the tumultuous social and political climate affected the game in 1968?

SP: In some ways, it’s a difficult question to answer. At a time when sports was highly politicized with the proposed Olympic boycott and the outspoken actions of men like Bill Russell and Jim Brown, baseball found itself rather insular—perhaps to its own detriment. But really two things stick out: The aftermath of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. In the case of the former, it not only delayed the start of the season, but, in some cases, both fostered dialogue on race in clubhouses.

In the case of the latter, it truly exposed the ineptitude of baseball’s leadership and the ascendency of the Players Association. “Led” by Major League Baseball Commissioner William Eckert, most teams were essentially left to decide on whether to play on the day of the funeral and the National Day of Mourning. The Mets refused to play on the day of the funeral and the Reds were essentially forced to. Players who declined to take part in games were traded or exposed to the expansion draft. At a time when Marvin Miller had already gotten through to the players about the true intentions of ownership, in my opinion, this marked a pivotal moment for the Union. From then on, it was an outfit to be reckoned with as the most powerful labor organization in professional sports.

SMR: Besides their standout achievements on the mound, what else connects Bob Gibson and Denny McLain enough to have them be your featured subjects in the book?

SP: Outside of having compelling lives worth exploring in detail, both stand for something in a game facing a world that seemed ready to let it go in 1968. Despite the idea that, as one writer put it, Gibson was a “new breed” of athlete, he is in fact the opposite. I see him very much in the mold of Ted Williams or Joe DiMaggio–a man who had little use for the press, or the fans for that matter, and had a steely devotion to his craft and winning.

I’m not saying that McLain didn’t care about his team. He did. He still blames his mysterious injury in the late stages of the 1967 pennant race for his team not making the Series. But even then he understood the idea of his “brand,” believing that his pitching provided the foundation for other venues, for greater fame. He saw the future–to an extent. The fact that he saw his baseball career as a transitional one to playing the organ in 1968, demonstrates that he could see the future of the modern athlete, but, as with most things in his life, was off.

SMR: Is it time for the Tigers to get back in good graces with McLain? Hasn’t he done his time?

SP: With the 50th Anniversary of their championship season, I’ve given much thought to this. The fact the Tigers won’t even honor McLain with a bobblehead and hardly acknowledge him is an affront to their own history. There would be no pennant, no championship without McLain. Though he didn’t perform as expected against Gibson, the man won 31 games and won both the American League Most Valuable Player and Cy Young Award. He pitched in constant pain, but he still pitched. And he was great.

That said, he’s done a lot to a lot of people. His criminal transgressions aside, he’s forever been at odds with the organization since he left the game. Denny’s done his best to antagonize old teammates when it really wasn’t needed and can be merciless in his criticism of current players. That said, at least for this year, the team should put certain things aside and recognize how special he was to a very special team. It would help a great deal if he put himself in good graces with the Tigers.

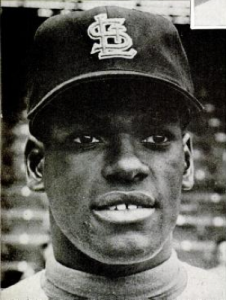

SMR: A lot of pitchers have been known for their intimidation, but Bob Gibson seems to be the one that fans think of first. Why do you think that is, and how did he earn that reputation, above all others?

SP: Let’s start with that stare. Gibson has said he was squinting, to see the signs from his catcher, but the effect is immeasurable. To look the part is one thing, but to live up to it, quite something else. Gibson wasn’t a head hunter. But he was resolute in keeping hitters “honest,” in keeping them from diving over the plate. His brushback pitch and ability to pitch inside with great command was unnerving to any hitter you talk to.

Then there was his treatment towards members of other teams. Any Cardinals player you speak to will tell you how gregarious Gibson was and how great a teammate he could be. But that was hidden by his outward animosity to a player who didn’t wear a Cardinals uniform. For the most part he didn’t fraternize at All Star Games, didn’t believe in establishing a closeness that others could use against him. He was someone who faced great adversity from the time of his birth and by his will and talent, reached a place of greatness. He wasn’t going to let anyone take that from him. And to this day, no one really has.

IBO Boxing Honesty and Integrity

IBO Boxing Honesty and Integrity